I’ve talked abut this a little in prior posts, but while I’m taking a day off to let my finger heal a little (there’s evidently a rough fret edge somewhere on my bass, so my pointer finger looks like it’s been sandpapered – I’ve taken a file to the treble side of the fret ends but I want to give it some more time, and I think I’m due for a fresh set of strings anyway) I thought I’d take a few moments to talk about bass editing.

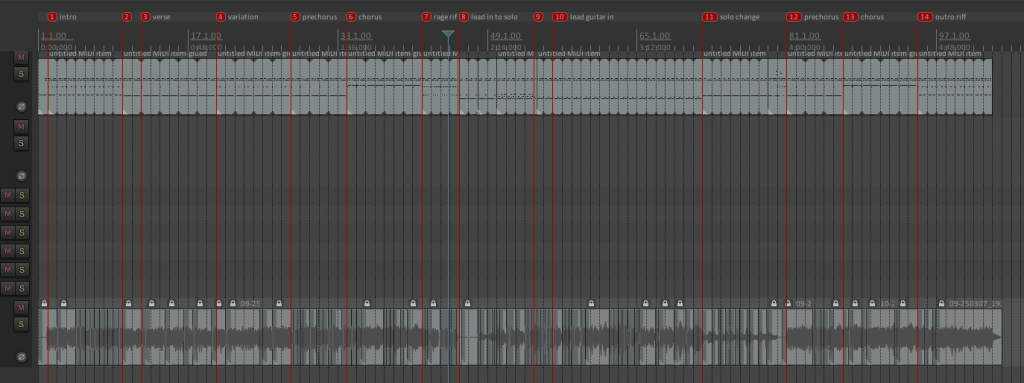

I thought a video might help, so here it is – I’ll explain in detail below.

So… Editing a performance feels dirty, and I’ll open by saying that bass is about the only thing I’ll do this to any extent on. On Zero Mantra there might have been a few edits to rhythm guitars here and there, but I can only remember a single note (I think it was the last note on the main solo of “The Mountain,” but I’d have to go back and check the file) where I nudged it a hair, because it was very behind the beat, and by the time it started to bug me, while mixing, it was too late to go back and punch in one a littme more in the pocket.

But, bass editing is pretty ubiquitous in most genres of “heavy” music, even when working with professional bassists at the very highest echelons of their craft (which as a bassist I assuredly am not), because if you’re chasing a mix with “tight low end,” one of the pieces of advice I always give when someone asks about that is SO much of this is a product of just having a really tight bass and drum performance. If your bass and kick drum aren’t absolutely locked in with each other, there’s no magic EQ or parallel compression or multiband compression preset you can throw at a mix to give it “tight low end.” That doens’t mean they all have to be perfectly on the grid, although when working with programmed drums that ARE programmed on the grid you haver a little less leeway, but they need to be absolutely grooving with each other, and any slop may not be really egregious when solo’d, but in a full mix that precision really matters.

I also vastly prefer slip editing, manually taking a note and sliding it back or forth into better alignment, to quantizing. There’s a few reasons for this – one, it forces you to start with bass tracks that are already pretty good, since the vast majority of the notes are going to be left untouched. Two, relatedly, because it’s a manual process, it really forces you to pick your spots – I talk about this a bit in the video, but I have a far higher tolerance for pushing or pulling the beat a hair on notes that aren’t one of the accented downbeats of the bassline, but the accented notes, i really want those to lock in with the kick. The result is you take a bassline that – hopefully – already sounds pretty solid, and adjust a handful of notes (in the songs I’ve finished tracking and editing, it’s probably been in the 15-40 note range), to make it even more in the pocket, but not sounding artificially, inhumanly even. As it stands, unless I just throw my hands up in frustration and call enough enough, I’ll probably finish this whole project by turning off snap to grid on my drum performance, and making the fills less perfectly even, but that’s a post for another time.

So, the basic workflow here – track your bass, and if you’re comping it together from a few takes, get it to the point where you have a single bass track ready to go that already sounds really good. Then, zoom in, and hit play, and both watch and listen – listen for any note that sounds audibly a little too early or late, and watch for any of your “downbeat” notes that are visually too early or too late, even if bartely perceptibly. Another upside of slip editing – it may make sense to simply watch and listen for a first pass without doing anything, to get a sense of how the notes “fall” on the grid. If the groove is such that your accent notes, or even one of them consistently, tends to be a little behind the beat but that just sounds great, that’s useful intel when you start editing and you’ll probably want to preserve that (even in cases where you accidentally WERE exactly on the beat on one of them, and want to introduce the slight behind the beat there that you were doing elsewhere).

The actual process you can see pretty well in the video, but essentialy once you identify a note, zoom way in and split the audio as close to a zero crossing as close to the very front of the attack as you can. Then, zoom out a bit and see where the slight lag resolves itself – I’ve found that, as we tend to have fairly strong internal metronomes, often times several notes in a row will be similarly behind the beat before an accented downbeat snaps you back onto the downbeat. so, find the attack of the first note that’s squarely on the groove (sometimes, the very next note; sometimes a few notes later), and split there as well. Then, go back to your initial attack, and slide the audio file forward or backwards until it’s squarely on the note. Pull the end of the prior audio file backwards until they align at the start of your edit, and at the end, take the audio file of your first un-edited note, and pull that backwards, extending it until it just touches the end of your edited audio (pulling the edited audio will start to add in the very beginning of the attack of the next note, doubling it and sounding, well, bad). This all sounds pretty confusing, but it makes a lot more sense watching it.

Always start by playing the best possible bass track you can, though – it’s possible to take a very mediocre performance and make it acceptably tight (harder if there’s also a lot of bvolume irregularities, since I suppose those you’d have to adjust every clip’s trim to even out, and likely you’d still need some heavy compression to get things right, but at least theoretically possible), but this would entail HOURS of work, and there likely wouldn’t be much “life” left in the finished performance. When in doubt, just doing a few more takes is always the right answer.

This is probably the final edit for the song in the video, working title “Gm Riff song” because I’m awesome at song names, and this is (so far at least) the most heavily edited bassline on this project, in part because there’s a lot of rhythmic 1st/3rd fret stuff and a bunch of sliding sessions, and for a guy used to a 25.5″ scale (and actively getting cut while tracking) this was pretty punishing stuff. And, while there are some parts with reasonably frequent corrections, there are also stretches of this running several bars or more that didn’t actually need anything. That’s always the goal, but an album is forever, and tight bass matters, so…